By Dr. Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui

Many have crossed Conn Creek on the way to Cardwell without giving much thought for whom the creek is named.

William George Conn was a Scottish immigrant who arrived on the lower Herbert in 1870, aged 51. He was a pioneer of the Clarence River, NSW, and afterwards took up Dillelah station near Warrego, western Queensland. Conn Waterhole west of Winton is named for him. He was described as ‘a brave and clever bushman and explorer’.

His second wife, Elizabeth Burrows, accompanied him to the Herbert when she was 31 years of age. They established a garden growing fruit, sweet potatoes and maize on the south bank of the Herbert, directly opposite Macknade Plantation on the north bank, where William did fencing work.

They carved a track from the south bank, across a group of sand islands — identified in a survey map of 1871 as the Elizabeth Group — to the north side. This track came to be called Conn’s Crossing. Once a new trafficable bridle path was cut from the Crossing to Cardwell in 1872, the previous track over the Seaview Range became obsolete.

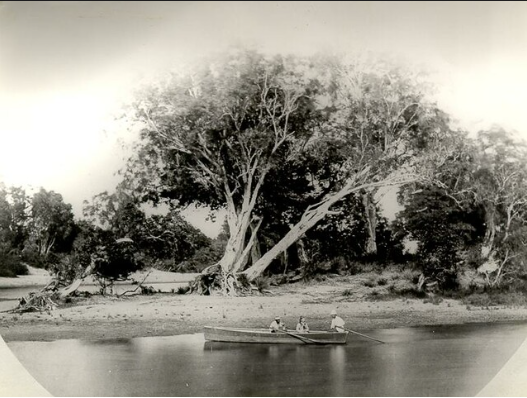

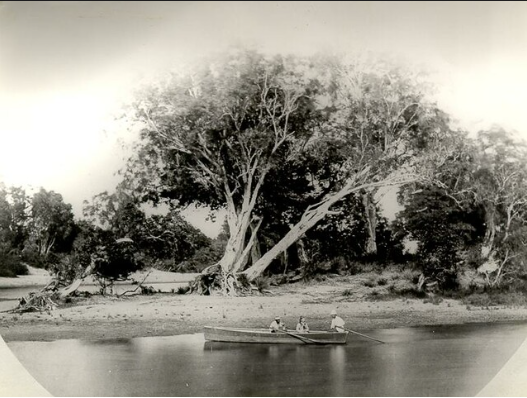

In 1873, they moved to an isolated selection 22.5 kilometres south of Cardwell that they named the Hermitage. They named the nearby creek, which was an access point between mainland and Hinchinbrook Island for the Indigenous people, Williams Brook (later Conn Creek). The Government paid William a small salary to keep the track open to traffic. Again, they established gardens, producing fresh produce for the Cardwell market, and offered refreshments to travellers.

Elizabeth was a hard worker. Planter Arthur Neame observed the Conn’s building a hut with William on the ground and Elizabeth on the roof putting on the thatch! By the end of 1873, their selection was well-established.

Neame and his fellow planters thought that the Conns were very foolish to settle where they had, with no other white settlers nearby. So concerned were they that William Bairstow Ingham invited William to come and work on his Ings plantation, but Conn refused.

There had been few violent confrontations between settlers and the Indigenous people on the lower Herbert, and Conn was of the opinion that if he treated them kindly, they would not interfere with him. So trusting was he that he traded vegetables for fish with those who paddled their canoes up Conn Creek to their property. However, misunderstandings began when vegetables were taken without the offer of an exchange of goods.

When his potatoes were getting close to being ready for harvest, William contacted Robert Johnstone and his Native Police detachment, who usually did boat patrols of the area. William made it clear that he did not want Johnstone to ‘molest’ the Aboriginals. Johnstone was so concerned for the Conn's welfare that he made a special patrol on horseback, where he found Elizabeth had taken ill. As she was too sick to travel with him on horseback, he promised to return the next day in a boat to take her to Gairloch, where there were ladies who could provide nursing care.

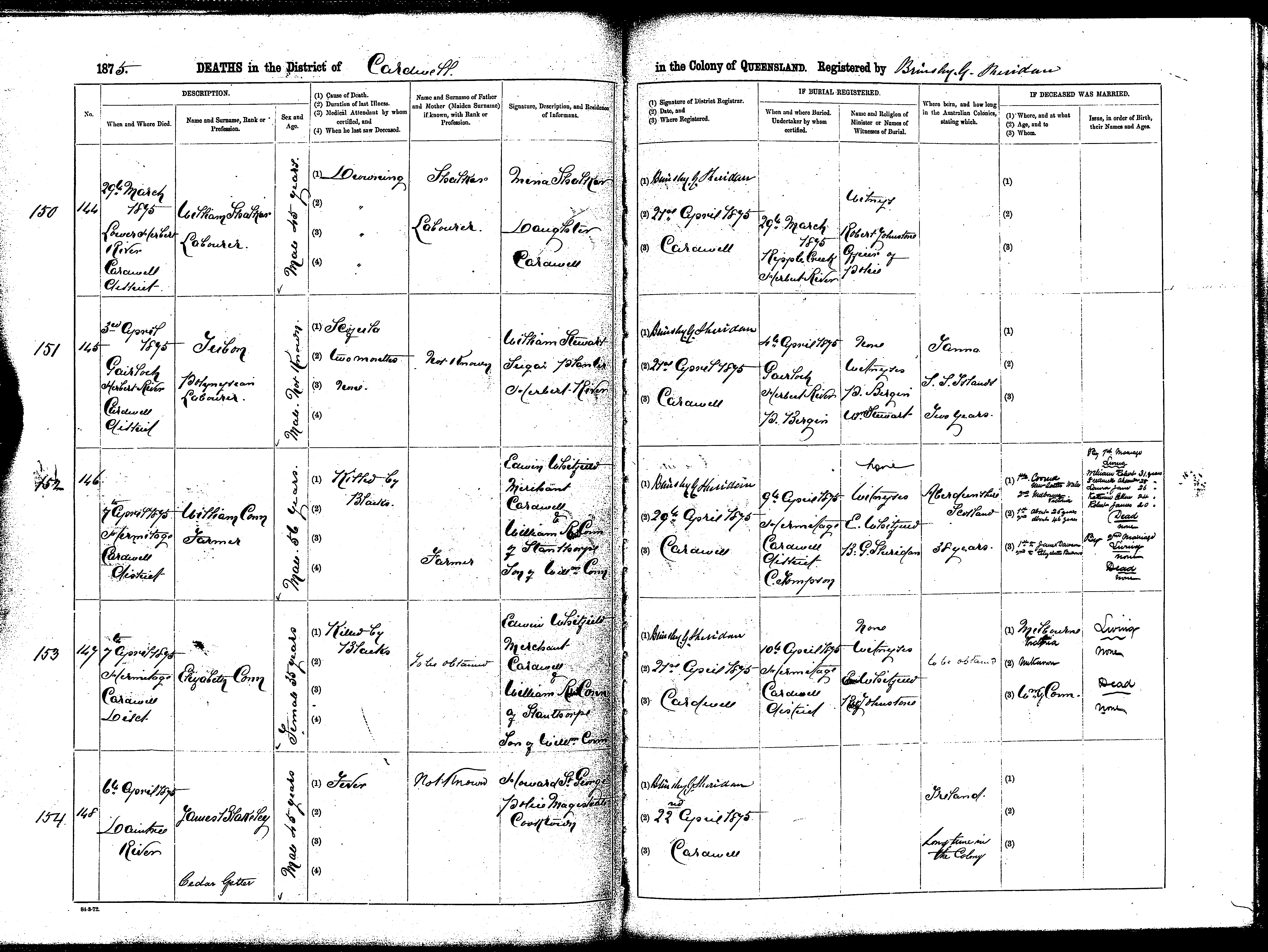

Unfortunately, due to bad weather and tidal conditions, Johnstone did not reach the Conn’s farm until sunrise on the morning of 7 April, in which time the Conns had been massacred. At the time of their deaths, Elizabeth was dressed and ready to leave with the boat patrol and had been preparing breakfast, while William was wheeling manure to his garden. There are numerous conjectures as to why they were massacred, but given their formerly amicable relations with the visiting Aboriginal people, there clearly had been a misunderstanding.

A group of Aboriginal people was located nearby with incriminating items in their camp. Retribution was immediate and merciless. Neame believed that the actual perpetrators got away, and those killed, including women and children, had nothing to do with the massacre.

The Conns were buried near their cottage, and a tree marked with the date and their names. It is said that the markers of their graves only disappeared in recent times when work on the adjacent government railway line was carried out.